Is the American public becoming less religious? Yes, at least by some key measures of what it means to be a religious person. (image, American Illiterati)

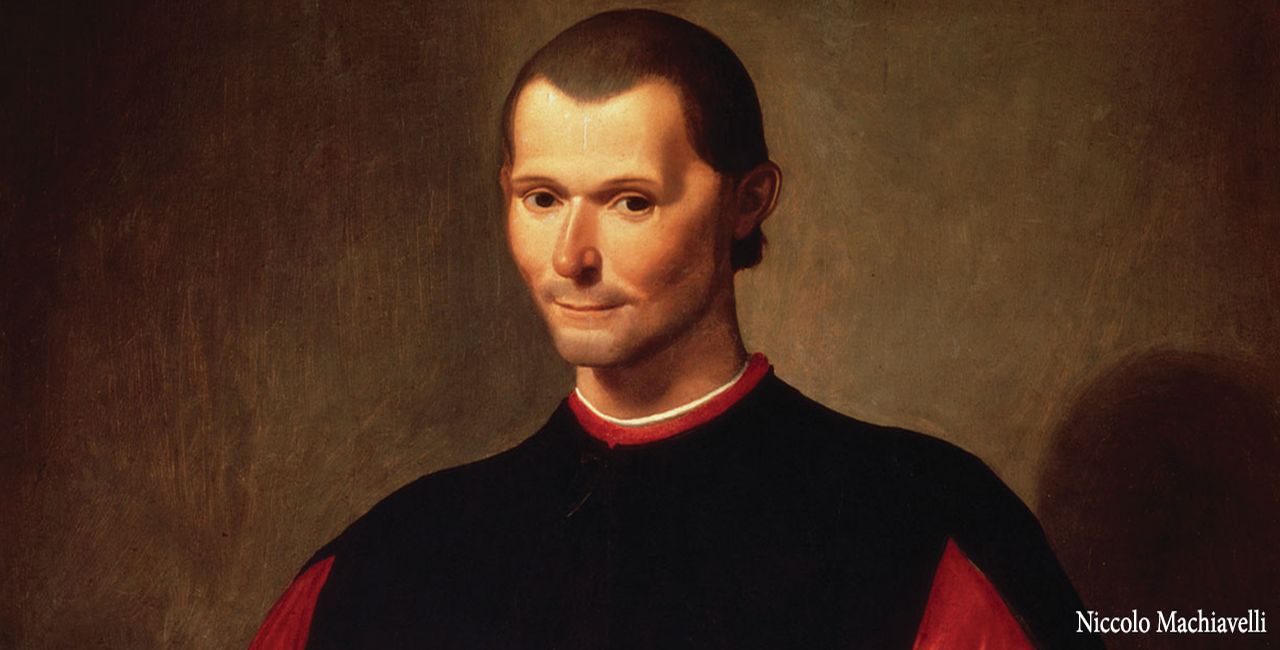

Renaissance political thinker Niccolo Machiavelli castigated Christianity for making its adherents weak. Looking to the next world, he charged, Christians forget their public duties in this world, leaving their communities weak in the face of their enemies. Early Christian martyrs were hardly cowards. There were martyrs in Machiavelli’s day as well, and as I write martyrs are being made every day as pious Christians are murdered by the thugs of the Islamic State. One wonders, however, given some recent trends, whether some Christians in the West—and especially their leaders—have not lost their courage, or even their faith.

A recent Pew Forum survey found that the percentage of Americans who identify with no religion at all has risen to 23 percent. Those stating that they are “absolutely certain” God exists has dropped to 64 percent. And there were small drops in religious observance as well. In comparative terms, this is not such terrible news. 89 percent of Americans continue to believe that God exists, and our rates of religious observance remain miles ahead of our European brethren.

Christianity in America may be faring better than in Europe, but it is truly frightening to consider where our current trends may take us. I am merely one among many observers who has noted increasing pressures in the United States to force religious believers to keep their faith to themselves, and even to violate it where it conflicts with the demands of secularization and social democracy. The clearest case in point, soon to be argued in front of the Supreme Court, concerns the Little Sisters of the Poor. This order of nuns objects to being forced by the Obama Administration to allow its health care plan to be hijacked to provide contraceptives and abortifacients to employees. The nuns correctly point out that this program is making them complicit in acts directly contradicting their Catholic doctrine. The Obama Administration responds that, because the nuns are being excused from actually paying for the abortifacients (instead the cost will be taken from more general program funds), they have no grounds for complaint—in essence, conscience be damned. The only way the nuns could avoid being forced to act against conscience here would be for them to employ and serve only other Catholics, in effect surrendering any public ministry in exchange for toleration from the state.

One of the more disturbing elements of such rules is their clear intention of marginalizing religious associations, forcing them into a religious closet, safe from the tender eyes of atheists and intolerant adherents of other faiths, as well as the federal government. The real danger here is that religious adherents themselves will internalize this false vision of religion as a purely private pursuit, giving up on their duty to share the faith and speak truth in the face of political and social power. An example of how wrong this can go is provided by the Anglican Church in England, according to a story in the Telegraph newspaper.

The Church of England is set to signal to members that speaking openly about their faith could do more harm than good when it comes to spreading Christianity. Stark new research findings being presented to members of the Church’s ruling General Synod suggest that practicing Christians who talk to friends and colleagues about their beliefs are three times as likely to put them off God as to attract them.

“Research” shows that people are “put off” by friends’ and colleagues’ discussions on religion? And what people, exactly? Non-believers.

Is this really news? Should anyone be surprised that people who self-identify as non-believers would rather not talk about God? What is truly shocking about this study is that the Church of England plans to take its findings to heart and use them in providing guidance to members of the flock in their interactions with nonbelievers. This is especially important in England, where a full 40% of the people do not even believe that Jesus existed and a third do not know a single person who is a practicing Christian.

The reasoning here lacks courage and even reason. It should be self-evident that most of those who continue to identify as nonbelievers when answering a survey are going to indicate that they do not like being told about other people’s faith. Not everyone is going to welcome religious witness—especially those who have been brought up to believe religion is nonsense at best. This is no reason to liken discussion of one’s faith to shouting on a street corner about salvation and damnation. Yet this is precisely what a Church of England official did in the newspaper story. Perhaps the leaders of this church might want to consider whether there is a problem worse than people being “put off” by religious talk in a nation in which a third of citizens do not know a single person who is a practicing Christian.

This is how religions die. To have lost so much ground among a people that once was overwhelmingly Christian, and to respond with embarrassment at the proselytizing of a tiny portion of one’s tiny flock, is a sign of terminal spiritual illness. It also, self-evidently, is precisely what nonbelievers and secularists want—namely, a quiet, untroubling Christian minority that will soon cease to exist altogether. This is where secularization naturally leads. When the faithful lose their voice, who will care what they believe? Who will join them, or even know that they exist?

In such times it is right to wonder whether Christianity really has become a religion filled with cowards. Christianity is not a coward’s religion, for its truth is hard, demanding self-denial and sacrifice in the face of earthly temptations out of simple love. Our brethren in the Middle East have shown us that some people of God remain able and willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for their faith. But things seem different in the (formerly) more peaceful West. What, then, is to become of Christianity in the West? If only cowards are left among Christians in the West, then here at least Christianity will cease to exist. Not completely, of course, for the truth never dies. But it could well die among a given people at a given time, becoming the faith only of a remnant with no public voice.

It is up to each one of us to see to it that we face the much lesser though more insidious temptations of cowardice in the face of mere, empty secularism to kill our faith. We must rediscover our courage so that we in the United States do not follow the trail being blazed ever so peacefully in Great Britain. And that means speaking out, speaking up for the Little Sisters of the Poor and others who work to live by and spread their faith, and to refuse, ourselves, to be silenced in the face of a regime that promises earthly goods to everyone along with freedom from the calls of the spirit, even as it punishes those who seek to heed that call.

Author: Bruce Frohnen

Author: Bruce Frohnen

Bruce Frohnen is a Professor of Law at the Ohio Northern University College of Law, where he teaches courses in Public and Constitutional Law, Jurisprudence, and Legal Profession. He is also a senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center and author of many books including The New Communitarians and the Crisis of Modern Liberalism, and the editor of Rethinking Rights (with Ken Grasso), and The American Republic.